According to Creswell and Guetterman (2019), eight steps are suggested to conduct a grounded theory research, especially if the research conforms to the systematic research design. Researchers taking emerging and constructivist design “might engage in alternative procedures” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p. 452).

Step 1. Decide if a grounded theory design best addresses the research problem

The first step of conducting a grounded theory is to determine if grounded theory will answer the research question.

Grounded theory is good to use when there are no exiting theories or limited theories regarding the process that’s of interest to the researcher; or there are theories that exist but they were created for a certain group of people that the research researcher is interested in.

For example, let’s say that there is no theory that exists in terms of the process of becoming a regular smoker while attending high school or college. A researcher might think what theoretical model could best describe the process of becoming a smoker in high school and college.

Step 2. Identify a Process to Study

The researcher needs to “identify early on a tentative process to examine the grounded theory study” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.452), although this process may be modified later in the study. “The process should naturally follow from the research problem and questions that the researcher seeks to answer” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.452).

Step 3. Seek Approval and Access

Ethical issues are always significant when it comes to conducting a study. Approval must be obtained from the institutional review board and from the individuals who will participate in the study before starting the research. For more details about ethical issues, please check out Chapter 7 – Collecting Qualitative Data (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.229-233).

Step 4. Conduct Theoretical Sampling

The researcher then recruits participants who have experienced or are going through the process of interest, which is as known as theoretical sampling—finding a sample of participants who have experienced the process that the researcher is interested in and can help develop a well founded theory. So in our example, it could be good to recruit smokers and former smokers in high schools and colleges.

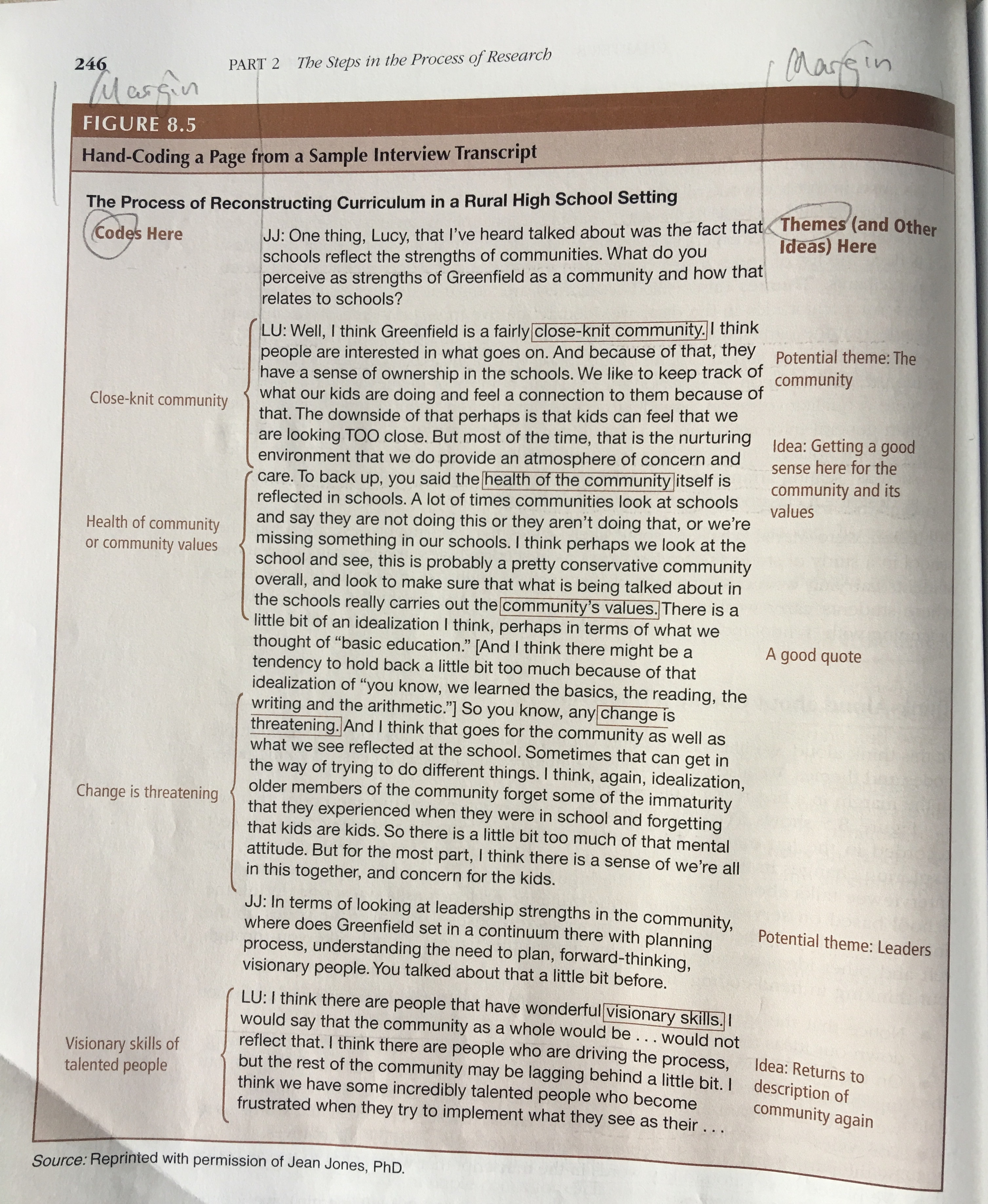

Step 5. Code the Data

“The process of coding data occurs during data collection so that you can determine what data to collect next” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p. 453).

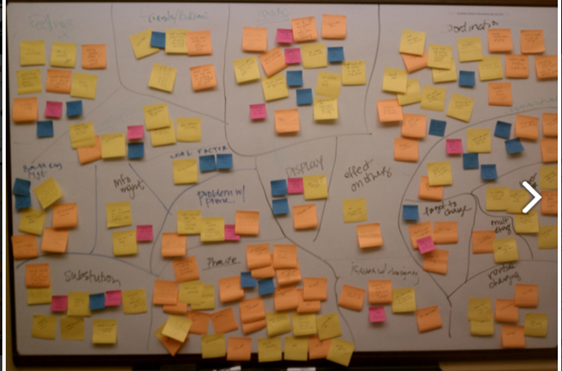

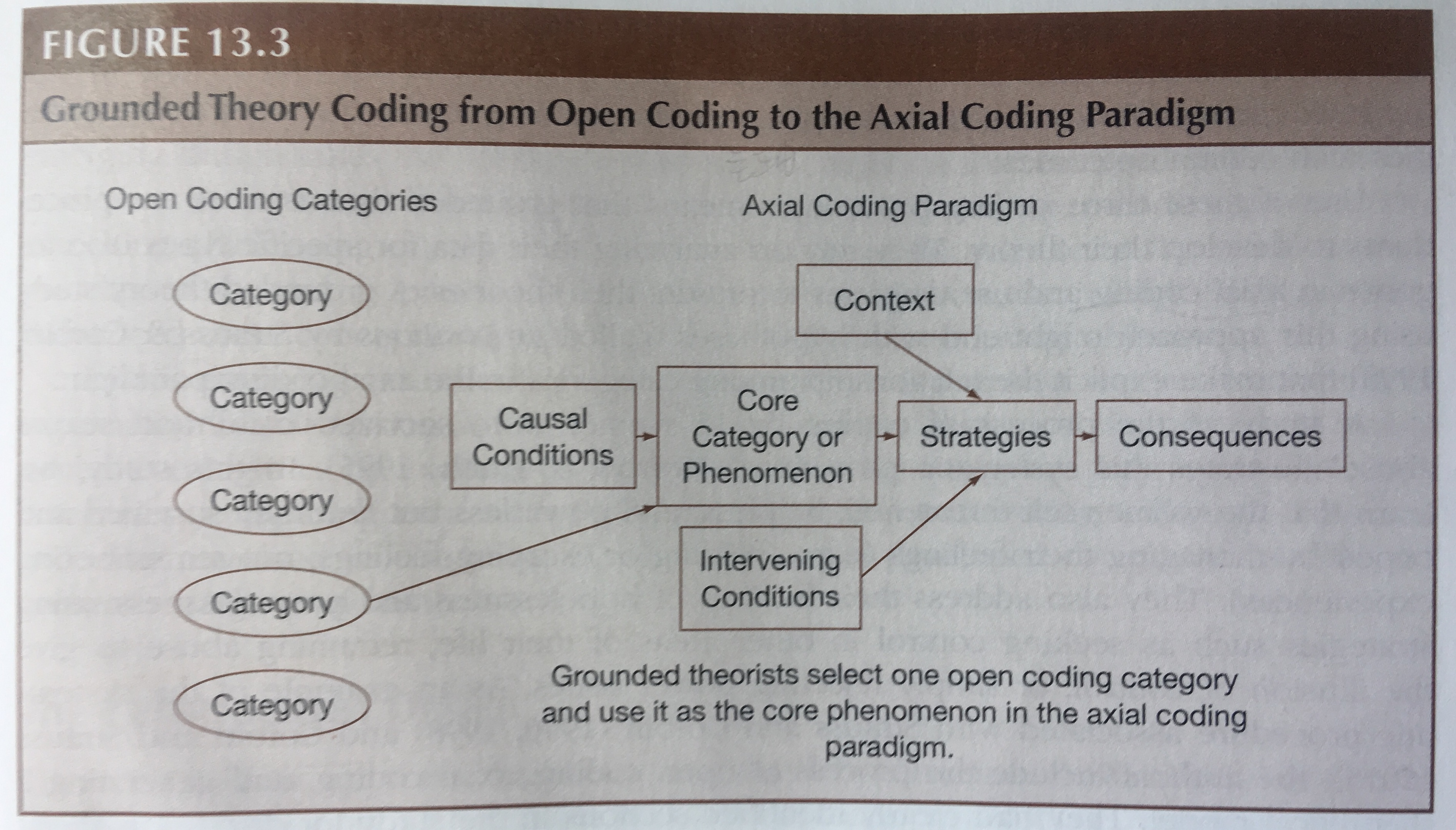

It usually starts with the identification of open coding categories and using the constant comparative analysis for saturation by comparing data and categories. Based on open coding, the researcher moves to axial coding and generates a coding paradigm, while causal conditions, intervening and contextual categories, strategies, and consequences are identified.

Step 6. Use Selective Coding and Develop the Theory

This step involves the actual development of the theory, including interrelating the categories in the coding paradigm, refining the axial coding paradigm, and presenting it as a model. Or, the researcher can write in a narrative that describes the interrelationships among categories (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.453).

Step 7. Validate Your Theory

It is important in the process to validate the findings, where the researcher actually checks to see if the data collected is reliable.

Based on the methods demonstrated by Creswell and Guetterman (2019) in Chapter 8 Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Data in the textbook, there are a couple of ways doing that.

One is member checking – to go back and talk to the individuals who have been interviewed to confirm the data collected accurately interprets their experience.

Apart from that, the researcher can collaborate from different individuals who are outside of your particular study but who might have expertise, and look at other ways that the data has been collected in the field and described as a way of validating the research, which is known as triangulation.

Alternatively, researchers can conduct discriminant sampling, where they “poses questions that relate the categories and then returns to the data and looks for evidence, incidents and events to develop a theory”; after developing a theory, the researchers “validates the process by comparing it with existing processes found in the literature” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.454).

Step 8. Write a Grounded Theory Research Report

“The structure of the grounded theory report will vary from a flexible structure in the emerging and constructivist design to a more quantitative oriented structured in the systematic design”. (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.454). It includes a problem, methods, discussion, and results; it reports the researcher’s “abstraction of the process under examination” (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.454).

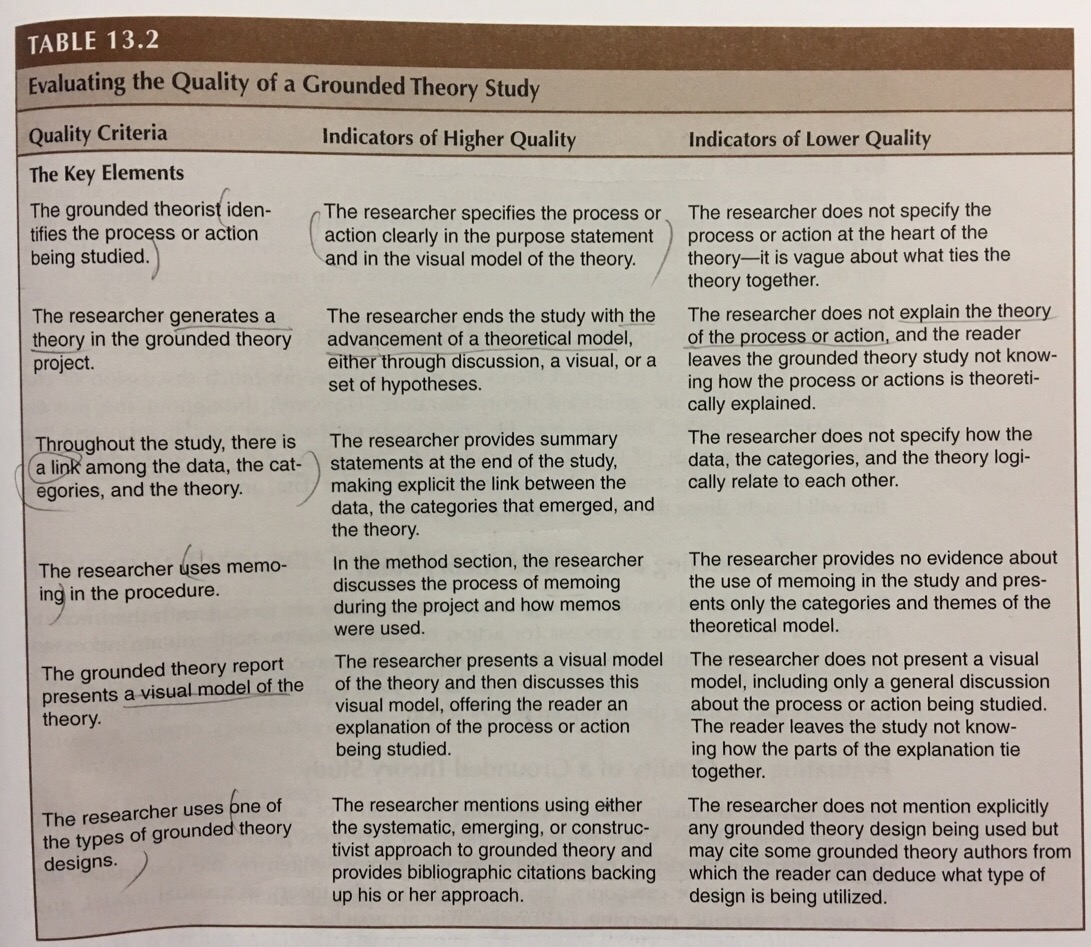

How to Evaluate Grounded Theory Research

Criteria for evaluating a grounded theory research is shown in the picture below (Table 13.2, Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p.455).

Strengths of the grounded theory

- Can use multiple types of data

- Provides an in-depth perspective

- New theories can emerge from coding the data into categories

The limitations of grounded theory

- Hard to recruit participants, depending on the process of interest

- Time to gather data

- Analysis can be difficult

- There may be researcher bias

- Researchers can feel ambiguous while conducting the study and the next step can be unknown

- To conduct a grounded theory, researchers must have patience.

The limitation with grounded theory can be hard to recruit participants depending on the process; it can take a lot of time to gather data, to analyze data, to come up with your model, etc. Data analysis can be difficult. It can be difficult to categorize and code all of that data; and there may be researcher bias in terms of the study and what categories are.

Moreover, because of small samples of participants, can we really say that their experience with that process is what has been felt by others although discriminant analysis helps to verify the model. If we are only dealing with a small number of participants in a particular area of the country, it can be problematic to claim that their experience with a certain process can really fully be pictured in a model and be applied to everyone else in the world.

Reference

Creswell, J. W. & Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson.