Three dominant types of grounded designs are introduced in the textbook by Creswell and Guetterman (2019): the systematic design by Strauss and Corbin (1998), the emergent design by Glaser (1992), and the constructivist design by Charmaz (1990, 2000, 2014). A comparison of the three designs (Table 13.1) is offered by the book (Creswell and Guetterman. 2019, p. 436).

Although the book introduces the three coding methods before getting into the emerging design and the constructivist design, I think it is more comprehensible if we look at the 3 designs together then the 3 coding methods.

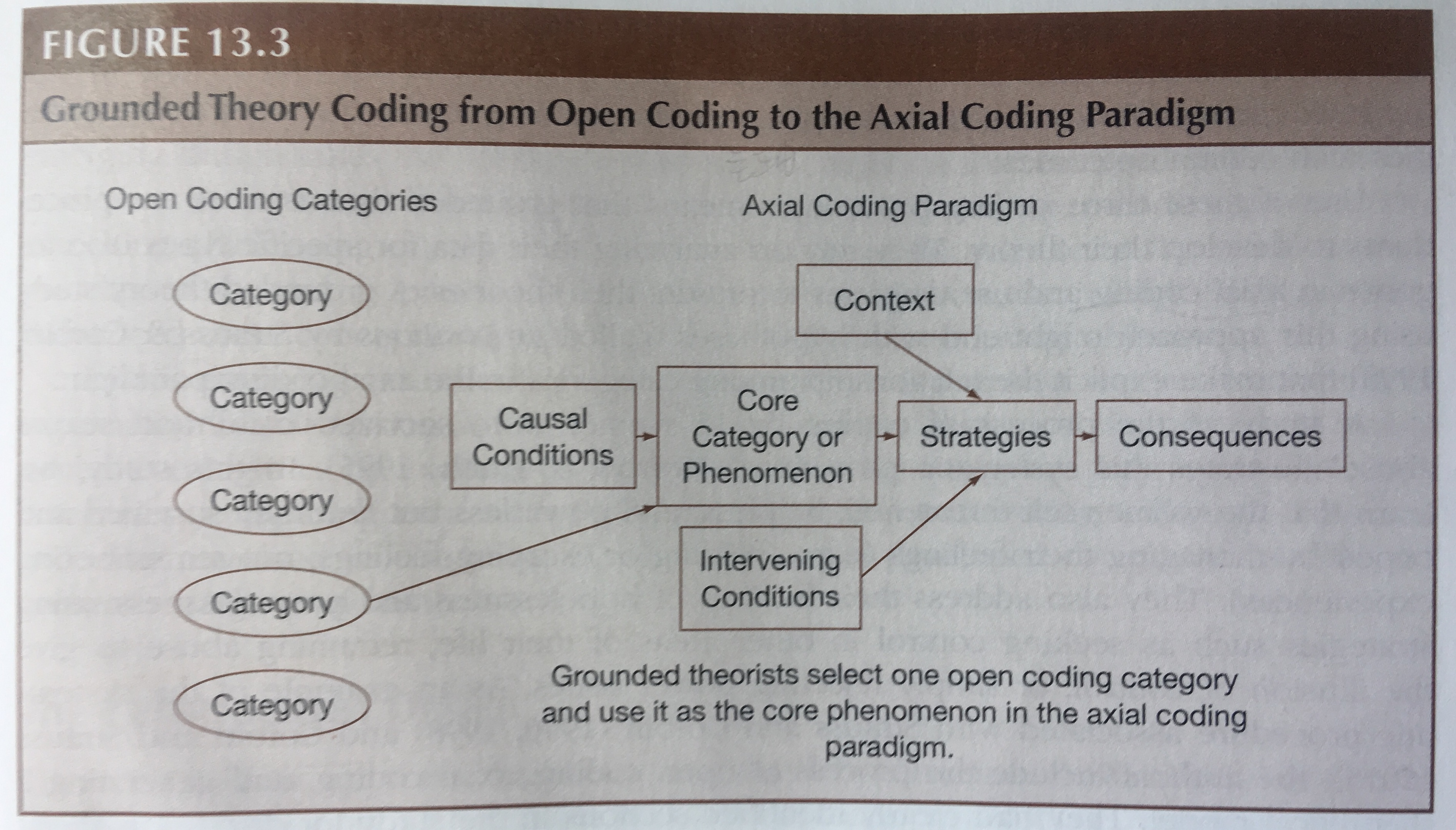

The picture above clearly shows how coding words in different grounded research designs. We will look at this in detail; now let’s just have a picture of the use of coding methods in grounded theory.

Three Grounded Theory Designs

1. The systematic Design

The definition of the systematic design in grounded theory by Creswell and Guetterman (2019) is quite inductive – “the use of data analysis steps of open, axial, and selective coding and the development of a logic paradigm or a visual picture of the theory generated” (p.436).

In the three phases of coding (open, axial and selective), the researcher starts with the most specific information they collected and summarize and move to the most abstract characteristics they were able to find through analyzing the data.

2. The Emerging Design

Compared to the systematic design proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1990), the emerging design by Glaser allows the theory to emerge from the data rather than forcing the data into preconceived categories. Glaser’s (1992) emerging design emphasizes on letting a theory emerge from the data. The generate theory should appropriately fit the data, should actually work, be relevant, and changeable when new data show up, which means in the process of the emerging design, the researcher collects data, immediately analyzes those data rather than waiting until all data are collected, and then bases the decision about what data to collect next on this analysis.

3. The Constructivist Design

Charmaz’s (1990, 2000,2014) constructivist approach emphasizes the views, values, and feelings of the people rather than the process. Whereas Strauss, Corbin and Glasser would focus on describing a process in their systematic or emerging design approach, the constructivist design would focus on how people felt during these process and try to extract meaning from the experience.

Example – A Research on Autism

Now let’s take autism an example to demonstrate how the three designs differ.

If we conducted a study on people with autism, the results would vary depending on the grounded theory design we used. If we used systematic or emerging design we would focus on the common process of acquiring and dealing with autism. However, if we used the constructivist design we would focus on how the people feel during their experience with autism and trying to determine what it means to have autism (Creswell and Guetterman. 2019, p. 441).

Three Coding Methods

There are three phrases of coding in data analysis, particularly when you use the systematic design in grounded theory, as it emphasizes on the inductive coding.

I will talk about more details for data analysis in my next post. Now let’s just have a big picture of the three coding methods in data analysis first before getting into the process of analyzing data.

1. Open Coding

The image above is from Crook’s thesis (2013).

In the first phrase, open coding involves “forming the initial categories of information about the phenomenon being studied by segmenting information” (Creswell and Guetterman. 2019, p. 436). For example, let’s take Crook’s (2013) study as an example: the research is to explore how the TESMC course supports the teachers in professional development (this is the thesis we evaluated in the second part of GSE 518). From the interviews, several teachers share what contributions the TESMC course makes in their professional development (see the first column of the image above). This information of the TESMC course from school for teachers’ professional development could serve as a category.

A Category can also have dimensionalized properties. According to Creswell and Guetterman (2019), dimensionalized properties means that there is a continuum on which the feature is seen. For example, from the image above, “active learning” (the second column of the image above) can be one of the several contributions of the TESMC course to teachers’ professional development. There are more contributions talked by Crook in her thesis.

2. Axial Coding

In the second phrase, axial coding involves taking one of the categories from open coding and making it the central phenomenon of the study. For example, if we are convinced that the TESMC course has a great value to the professional development for teachers, this would become the central phenomenon.

According Creswell and Guetterman (2019), the The categories in the research can be one of the following:

- Causal conditions: what influences the core category

- Context: the setting

- Core category: the idea of phenomenon central to the process

- Strategies: what is influenced by the central phenomenon

- Intervening conditions: what influences the strategies

- Consequences: the results of using the strategies

This is also called the coding paradigm.

The picture above, Figure 13.3, (Creswell & Guetterman, 2019, p. 439) shows the coding for systematic grounded theory and the interrelation among the various categories.

3. Selective Coding

Selective coding is the third phrase of coding and involves taking the coding paradigm and converting it to written text. It involves “writing out the story line” (Creswell and Guetterman, 2019, p.439) in which the process happens and providing an explanation. In this phrase, the researcher “examin how certain factors influence the phenomenon leading to the use of specific strategies with certain outcomes” (Creswell and Guetterman, 2019, p.440). In other words, the researcher needs to take all of the information involved with interviews, developing an axial coding paradigm, and finally writing this down in coherent language as a theory.

References

Creswell, J. W. & Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Crook, T. A. (2013). A case study exploring the value and relevance of using the teaching ESL students in mainstream classrooms (TESMC) course for professional development related to teaching English to speakers of other languages with mainstream teachers of English language learners in international schools.